Vandals had scrawled the words "Morton Thiokol Murderers" on a railroad overpass on the road out to the Thiokol plant. Many Thiokol workers lived in Brigham City and the town was taking the disaster hard. 19, I headed to Brigham City, Utah, the town closest to Thiokol's remote plant. I tried again over the next several weeks, getting a few more details but little substance. But none would consent to a detailed interview or on-the-record conversation. Each confirmed the notion of a coerced launch approval.

I reached two of the engineers and the wife of a third on the phone. A source who asked to remain anonymous told me that Morton Thiokol was "coerced" into approving the launch, after the company's engineers voiced their objections. It wasn't long after the Challenger explosion that word of a pre-launch argument leaked out. Neither has released us from that pledge of confidentiality, so they shall remain unnamed. "I'm so torn up inside I can hardly talk about it even now."īoth engineers asked that we not reveal their names in 1986. "I fought like hell to stop that launch," one of the engineers told Zwerdling. The night before liftoff, these two Thiokol engineers, along with several colleagues, tried to convince NASA to postpone liftoff. The engineers had resisted the launch, had recommended against it, citing the "blowby" in an earlier low-temperature launch and studies of the elasticity of the o-rings. When the door finally opened, Zwerdling heard a remarkable tale, matching in almost every detail the story that simultaneously unfolded to me in Utah. He first spoke through the door, weeping at times. This would be the coldest launch ever.Īs I sat with that despondent Thiokol engineer in his home in Utah, my colleague Daniel Zwerdling stood outside a hotel room door in Huntsville, Alabama. In fact, there had been evidence of leakage, what the engineers called "blowby," on an earlier shuttle flight.

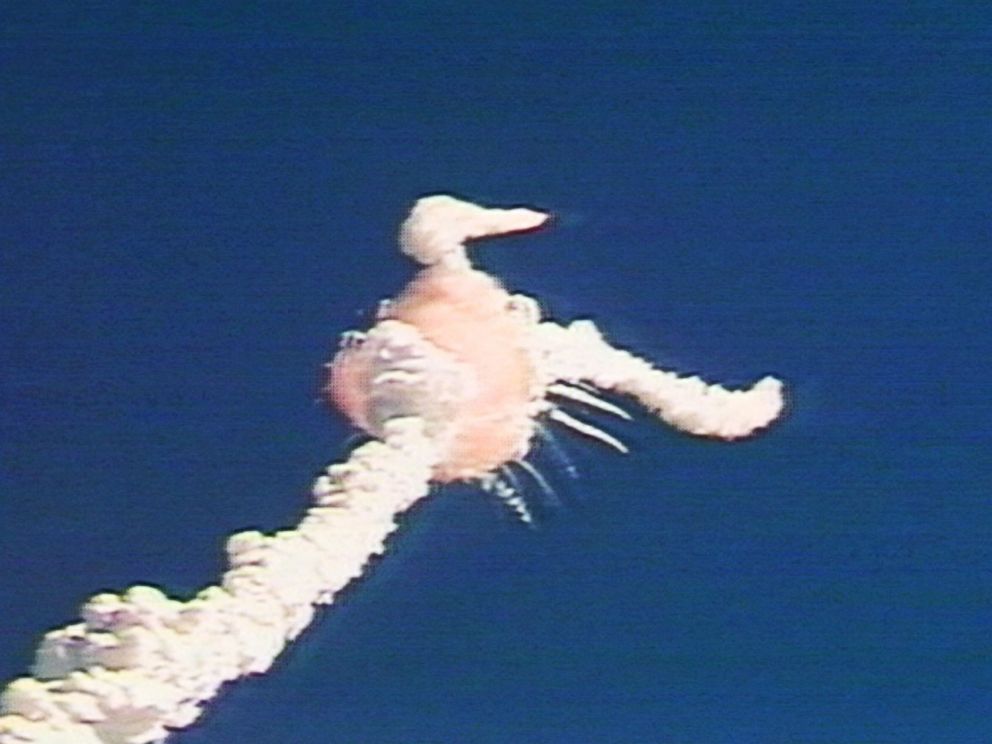

They knew that stiff o-rings didn't provide a secure seal. They knew that cold overnight temperatures forecast before launch would stiffen the rubber o-rings. Some of those Thiokol engineers expected o-ring failures at liftoff.

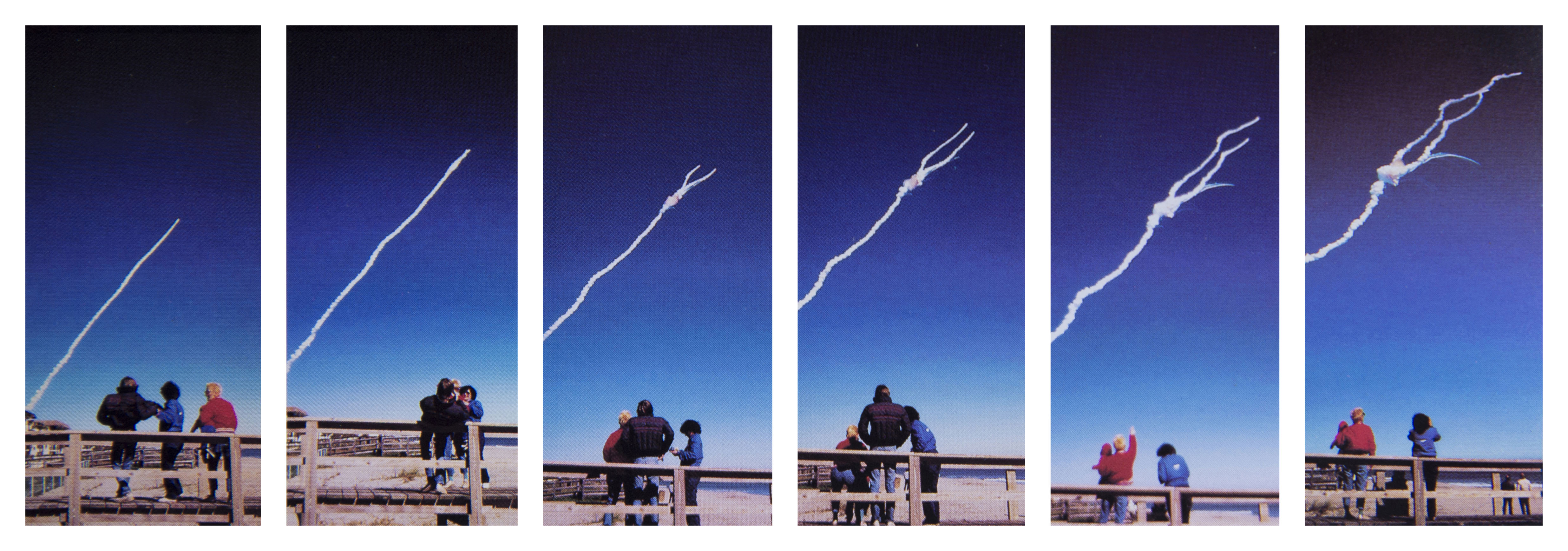

Rubber o-rings lined those joints and kept burning propellant from leaking out. The forces of liftoff tended to pull the cans apart slightly where they joined. The rockets were like stacked metal cans stuffed with highly explosive propellant. They worked for Morton Thiokol (now ATK Thiokol), the Utah-based NASA contractor which produced the solid rocket motors that lifted space shuttles from their launch pads. That engineer and several others were not surprised when Challenger exploded 73 seconds after liftoff on Jan. "I should have done more," the engineer told me, shaking his head. It played and replayed on television screens, endlessly it seemed. Three weeks later, in a living room in Brigham City, Utah, a proud space program engineer watched the scene again.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)